Learning from weeds July 11 2020, 0 Comments

With our world in such an unusual condition now, I find the plant world a sane and stable refuge. My garden is a stress-reliever in the best of times, and it is a special help to me now. With our unusually cool and moist weather last month (Is anything usual?), the plants have done well. There was a bumper crop of cherries, and my flowers have been blooming enthusiastically since early spring.

The weeds have also done quite well. Weeds are a good source of material for botany lessons, and they are found all over, in city sidewalk cracks as well as gardens. Their adaptations make them very abundant. There are few problems with uprooting them and dissecting them. It is a good thing to learn your local weeds and know some of the lessons they offer.

First, perhaps I’d better say what I mean by a weed. It is plant that grows where it is not wanted and displaces or damages the plants I want to grow. In my garden, some violets are weeds because they spread all over. The one below is especially weedy.

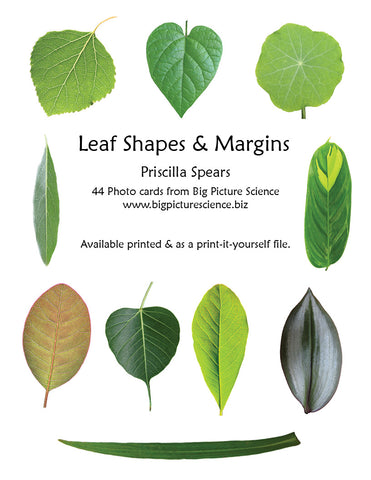

Weeding is applied leaf shape work. Learning to recognize the local weeds is a great gardening skill for children or adults. First, children have to recognize the leaves of desirable and undesirable plants. It takes time to carefully observe the garden, and it is important to have a guiding adult’s help to learn what to keep and what to uproot.

I don’t mean that children have to give the weed’s leaf shape a formal name. Many leaves can be recognized by overall appearance, and noting the leaf’s traits, such as lobes, teeth, or a particular surface texture, can help one identify the plant. Whether the leaves are opposite, alternate, or whorled around the stem is also an important trait, as is the overall size and shape of the plant.

Weeds helps hone one’s observation skills. One key to being a great weed is to escape detection for as long as possible. If your children want to find weeds to study, they will have to look carefully. The spotted spurge is a champion at hiding. The dark markings on its leaves make it hard to see against the soil, and it is a prostrate plant, one that grows very flat against the soil. The overall look of this plant, its milky white sap, and its leaves are a good way to recognize it. Warn children that the sap is very irritating, which brings up another reason to know your weeds – learn the hazards that children may encounter handling them. They will need gloves if they are pulling or digging spurges.

Every spring, I pull the dozens of little maple seedlings, which I recognize by their toothed, opposite leaves. There isn’t enough room for them to grow where they have sprouted. The oak seedlings from acorns that jays and squirrels planted sprout leaves that may not look like a mature oak (see below). I want to pull the little oaks quickly before they grow deep roots and are harder to remove so I need to look for their young leaves.

Weed roots can provide interesting material for study, particularly if you can extract most of the root system. Here is a blackberry seedling that I pulled from soft soil. I was impressed by the length of its tap root. Note the transition from the stem to the roots. To make sure the weed doesn’t grow back, you have to get all the stem and the upper portion of the roots. If the top of the root remains in the soil, it can grow new shoots.

If you pull up a red-root pigweed, you’ll recognize it. It is a member of the notoriously weedy amaranth family. The plants are capable of making thousands of tiny seeds.

You can make illustrations to help children recognize weeds by photographing the plant or by placing a specimen that you have collected between two acetate sheets and scanning it or photocopying it. The acetate will help keep the scanner or copier clean.

A field guide to weeds is a great help for identifying them. There is the excellent Lone Pine Guide, Weeds of Canada and the Northern United States for those regions. In the Midwest and Rocky Mountain regions of the US, Weeds of the West, published by the University of Wyoming, is very useful. Northwest Weeds by Ronald J. Taylor is a helpful guide for that area of the US. If you are in the western US, the children’s book, Outlaw Weeds of the West by Karen M. Sackett, is a good resource for learning about weeds and their adaptations. If these do not cover your area, look for a local weed guide.

Have fun getting down in the weeds!