In the Northern Hemisphere, many schools are beginning their new year. Others around the world are in the last term for their school year. Wherever you are in your yearly cycle, please make time for fact-checking the science materials your children use in their classroom.

By fact-checking, I mean that you read the text and look at the illustrations for the learning materials that children will see. Then you confirm the information with reliable references. This sounds fairly straight-forward, but it is time-consuming, and therefore few people do it.

Fact-checking is absolutely critical because anyone can print materials, whether or not they are familiar with the subject matter. The visual impression and first information that children get from a chart will stick with them, whether it is accurate or not.

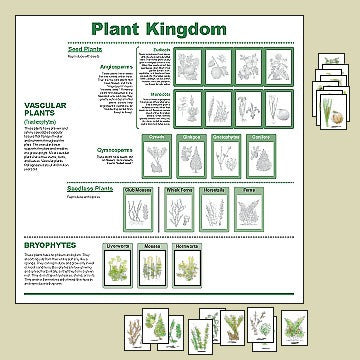

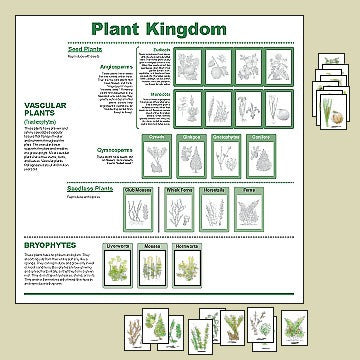

Some authors of Montessori materials are conscientious and carefully research their works. The illustrations on this page are the animal and plant kingdom charts from InPrint for Children, a company which always produces quality materials that are beautiful and accurate. Its owner and designer, Carolyn Jones-Spearman, is a perfectionist, and it shows in her work. That is why I partner with InPrint and sell those materials.

Unfortunately, some authors produce materials with errors or misconceptions because they don’t take time to learn the subject matter or because that is the way they’ve always done it. Some purchase a company and continue to provide its same materials without evaluating them. Certainly, there are commercially available materials that are not suitable as learning materials for children, either because they are outdated, or present false or misleading information.

It appears that all adults who create materials for elementary Montessori children do not have a good grasp of science subject matter. Running a business, printing materials, and marketing them are important skills for a business, and some do that well, even though they are not good at writing or researching valid content. Just because the ads look good, don’t assume that the materials are great.

I suggest that you go over all the materials you will provide to the children, whether those materials are newly printed or older ones that you have in the closet. If the volume is too great for you to cover, perhaps you can get help from older elementary children or secondary students. Children should see fact-checking as a useful activity for anyone.

First, look at the material and its illustrations. Do the illustrations give a clear picture of the subject? Are they indeed examples of the subject? I have seen charts illustrated with organisms that are not the ones being described. I have also seen superficially attractive charts that had artistic but wrong or confusing illustrations. A scientific illustration should clearly depict the features that children need to learn.

Next, read the text. Are there spelling or grammar mistakes? Does the language read smoothly, and is it concise? Most importantly, does the text convey the information clearly? The descriptions on a science chart shouldn’t be a dull list of facts, but they should not be wordy or have convoluted language either. Authors for children need to be held to the same standard of writing as a professional writing for adults. It should be our goal to provide children with examples of good writing in all their materials.

What do you do if you find less than acceptable content in a material? I strongly suggest that you write the publisher or seller of the material and give them a description of the problem. If the content needs to change, as most of biological classification has done in the last 20 years, authors need to know this. Don’t be shy in asking for a corrected version. See how the seller responds. You may wish to return the material and ask for a refund. It shouldn’t matter if you have had the material for a while. If it has serious defects, then you should be able to return it, and you may wish to warn your fellow teachers. Until teachers put pressure on the publishers of Montessori materials to get rid of their mistakes, commercially available products are not likely to improve.

That being said, if you find a simple typo, try putting a white sticker over it and correcting it yourself. The publisher would probably be grateful to have your corrections, but this is not the sort of thing that should cause you to return a material.

I certainly welcome reports of any spelling or grammar mistakes in my works. I seldom get them, however. When I went back through my Plant Lessons book before I printed it last spring, I found a number of grammar mistakes, often having to do with the placement of commas. I’m still learning and striving to improve my writing skills.

If you have specific questions about the contents of a science material, and you have not been able to find the answers on your own, you may email your questions to me. I will try to answer them, although I can’t guarantee how quickly. I'll address finding reliable sources of information in a future blog.

Priscilla

Many people are surprised to learn that broadleaf trees are flowering plants. It is true that most of them do not have the showy blossoms that people associate with the word “flower.” Members of the rose and magnolia families aren’t subtle with their flowers. Any sighted person can tell they are blooming.

Other kinds of trees may have quite inconspicuous flowers. The blooms may be so subtle that most people, including children, do not notice them. Help your children see these structures as they happen briefly in spring.

The red maples are among the first to bloom. Maples have a variety of flower structures and reproductive strategies. Some have yellow-green flower clusters that have both staminate and pistillate flowers. Others make extra staminate flowers and only a few with pistils.

Red maples are mostly dioecious – they have staminate and pistillate flowers on separate trees. I say “mostly” because I have seen and read other reports that a tree of one sex will sometimes have one branch that has the opposite sex flowers. This probably helps insure that pistillate flowers will receive the pollen they need to make seeds.

When the red maple starts to bloom, you may notice a red tint on the branch tips. If you can find a branch that is low enough for you to examine (try binoculars if the branches are too high), you will find one of two types of flowers. Neither has petals; both are small. The pistillate flowers (left) have two-branched stigmas showing. They are more intensely red than the staminate flowers (right), which look like a tiny pom-pom in reddish pink.

After the flowers bloom, the staminate flowers fall off. They have released their pollen, and their work is done. The pistillate flowers that received pollen continue to grow, and they develop long stalks with their young fruits at the end, often still bearing the drying stigmas. The fruits will become the maple keys; two grow joined together, but they split at maturity. This makes a maple fruit a schizocarp. Its two sections are samaras, winged fruits that the wind disperses.

Elms are another family of early bloomers. Their flowers are tiny, just two little furry stigmas surrounded by stamens. The developing fruits – again they are samaras – often color the tree a spring green and then turn brown before the leaves are completely unfurle d.

d.

Ask your children to think about the adaptation of blooming early, having wind-pollinated flowers, and having wind-dispersed fruits. They may be able to reason that the trees must bloom early so that their leaves won’t interfere with the pollen transfer. Some trees, like the elms, even disperse their seeds before the leaves block the wind from the mature fruits.

Swelling buds and developing leaves and shoots make great subjects for botany observation. Enjoy them with your children as the shoots and the spring develop.

Priscilla, April 9, 2018

Certain materials are “classic” in Montessori classrooms. The external parts of the vertebrate animals are one of those essential materials. This set traditionally has a horse as the example of a mammal, and almost all commercially available card sets for study of the vertebrates uses the horse.

My question is “why?” Unless we try to understand Maria Montessori’s purpose in the design of her materials, we can easily get caught in a web of tradition that keeps us from serving children’s learning needs to the best of our ability.

Here is my best guess on the horse as the mammal example. The horse was present in the lives of children all over the world until about 1920. It didn’t matter if they lived in a city or on a farm. When Maria Montessori first created her materials, the mammal that most children would see in their everyday lives was a horse. That has changed for most children. The horse is still used for transportation in some rural areas, but this animal is now more likely to be seen in a hobby or leisure situation. Most children in the United States do not see a live horse with any regularity.

What mammals do children see today? Dogs and cats would likely top the list. Classroom pets like gerbils, guinea pigs, or hamsters are common enough. Why don’t we use one of these for the example mammal? Children are more likely to be interested in learning about an animal they can experience, and learning about the care of that animal may also be very relevant to them.

Should we get rid of the “Parts of a Horse” cards? Probably not. There is nothing to keep you from having additional examples after you study the first one. Some children do see horses regularly and will be very interested in learning their parts. Others could have their horizons expanded by seeing additional examples.

What about the other vertebrate examples? The frog as an amphibian is about as good an example as a newt or salamander. The latter two are harder to observe in nature, but they can be kept in the classroom, probably with fewer problems than keeping a frog. It depends on the frog. Some can be escape artists – voice of experience here.

The turtle probably became the reptile of choice because it is less intimidating than a snake or a lizard, but a lizard gives a better look at the basic reptile body. Turtles are quite derived – they have changed a lot from their ancestors. They still have the scaly skin and lay eggs, so they work.

At some point, the crocodilians (crocodiles, alligators, caimans) need their own category. They are more closely related to birds than they are to the squamates (snakes and lizards). Both crocodilians and birds belong to the archosaur branch of the reptiles. Now that this is known, even children’s books point out the similarities. Both birds and crocodilians make nests, vocalize, and care for their young. They both have four-chambered hearts as well.

These two are closer cousins than either is to a lizard.

Using a perching bird for the example of the feathered vertebrates works well. It is worth asking, however, what birds children see. Maybe they see chickens on the school grounds. Maybe it is song birds that come to a feeder. Maybe it is a pigeon in the city. Maybe it is caged bird in the classroom. Going back to a real bird is an important step to make learning the parts into living knowledge.

Finally, the whole collection of vertebrates should be called the groups of vertebrates, NOT the classes of vertebrates. Biologists haven’t placed fishes into a single class since about 1850. The former classes were jawless fishes, cartilaginous fishes, ray-finned fishes, and lobe-finned fishes. That’s much more than children need at the beginning of their studies. The classroom fish tank can house valuable examples of ray-finned fishes, and that’s a great launching point. After all, ray-finned fishes are more than 99% of all fishes.

You can look that fish in the eye and say to it, “You and I shared a common ancestor, back in the beginning of the Paleozoic Era.” You can tell the amphibian that you shared a common ancestor with it back in the Devonian Period. Not long (geologically speaking) after that in the Carboniferous Period you shared a common ancestor with birds and reptiles, the other animals that reproduce on dry land, which are known as the amniotes.

It’s all in the ancestors and the great evolutionary journey. Enjoy the trip.

The timeline of life is a vital part of cosmic education. It gives children a vision of how life has changed through time and an important perspective for appreciation of today’s life on Earth.

I have been frustrated with the many errors and misconceptions that are portrayed on the traditional Montessori timeline of life. Another material, not from the Montessori world, has come to my attention. It is from What on Earth? Books, https://www.whatonearthbooks.com/us/ . Author Christopher Lloyd and illustrator Andy Forshaw have done several “Big History” type timelines. These publications can give children a valuable framework of how life has developed and changed through time.

In order to show a variety of life and tie it into human civilization, the timeline uses different timescales across its length. This could lead children to a false picture of the time elapsed between the events depicted. You can help them understand the true duration of the various geologic time periods if you display the time periods to scale above the timeline in the What on Earth? Wallbook of Natural History: From the Dawn of Life to the Present Day.

I did this for the 2.3 meter-long edition, published 2013. This book is 16.5 inches or 42 cm tall. I made a timeline that shows the true proportions of the geologic time periods. The second strip of paper beneath it shows the time periods as shown on the timeline. Here are the views from the formation of the Earth end and the present end. You can see that the Hadean Eon (black), Archean Eon (yellow), and Proterozoic Eon (pink) portions have vastly different shares on the two scales.

For example, the Hadean Eon is 31 cm long on the actual timescale, and 3.4 cm long on the timeline. The Cenozoic Era is 3.4 cm long on the actual scale, and the Holocene Epoch would be microscopic. On the What on Earth timeline, the Cenozoic Era is 46 cm, with 23.5 cm of that being devoted to the Holocene and Anthropocene. (If you would like the measurements for my two timelines, please email me.)

This timeline gives most of its length to the Phanerozoic Eon (Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic Eras), which is appropriate. The traditional Montessori timeline of life shows the events of the Phanerozoic Eon, even if it does not carry that label. When one looks at the What on Earth timeline from the end that shows the present, the Cenozoic Era has internal scale changes for emphasis on human events.

Nevertheless, I think the What on Earth timeline would be a good introduction to the changes in life through time. Having the life in the oceans shown separately from life on land helps children keep track of the two different environments. There are a few things you will need to correct/explain. The synapsid lineage is shown, but it is called “mammal-like reptiles,” an older term that paleontologists have dropped. Likewise, I would change the term “dicots” to “eudicots,” the term botanists use. Eudicots (true dicots) are the old dicots minus the magnoliids. At least the eudicots are there on the timeline, along with a good array of accurately portrayed prehistoric plants, a part that is often missing from timelines of life.

The What on Earth book or timeline is available in several sizes. There is a newer edition that is smaller and 6 feet long. You may need the magnifier, a flat, plastic Fresnel-type, that comes with the book, to read all the fine print. The timeline is available in a larger, 10-ft. edition as well. It is available on Amazon or on the What on Earth website. https://www.whatonearthbooks.com/us/shop/nature-timeline-posterbook-u-s-edition/ . It costs $40-50, and the smaller version costs $15-$20. At present, the nature (history of life) timeline is available in Japanese, Chinese, Korean, Taiwanese, American and Dutch. German, French, and Italian are in the works. The What on Earth Big History timeline is available in 15 languages, but the history of life takes up only about a third of it with human history displayed on the rest. See the What on Earth website of further information.

You may choose to make your own timeline. If so, my publication, Outline of Geologic Time and the History of Life, can help you. See https://big-picture-science.myshopify.com/collections/big-picture-science-digital-downloads/products/outline-of-geologic-time-and-the-history-of-life .

Happy explorations of life through time.

For many years, I have promoted the idea of structuring botany around the flowering plant families. It’s a practical way of addressing the diversity of the angiosperms, and it is knowledge that works in many places and at many levels. For instance, organic gardeners need to know the families of vegetables so that they can do the proper crop rotation and fertilizing. Plant identification is much easier if one can determine the family. Flowers in the same family share certain features, so it is quite possible to recognize the family even if you have never seen that species before.

To help you with your botany studies, I’ve just revised and expanded my PowerPoint slides on flowering plant families. This file is a pdf that can be printed to make letter-sized posters of 20 flowering plant families. The slides include text that describes the features of the flowers, and they show photos of family members. To round out this material, I’ve added a representative photo of 48 other families or subfamilies from all branches of the angiosperms.

To help you with your botany studies, I’ve just revised and expanded my PowerPoint slides on flowering plant families. This file is a pdf that can be printed to make letter-sized posters of 20 flowering plant families. The slides include text that describes the features of the flowers, and they show photos of family members. To round out this material, I’ve added a representative photo of 48 other families or subfamilies from all branches of the angiosperms.

Perhaps you would like to do a Tree of Life diagram for the flowering plants. There is a good one in the book, Botanicum by Katie Scott and Kathy Willis. It is part of the Welcome to the Museum series from Big Picture Press (no relation to Big Picture Science), and it was published in 2016. The branches are correct on the diagram (pages 2 and 3), but they have just one example for each branch, and the orders are not stated. The example represents a whole order, which leaves out a lot. For example, the rose order, Rosales, is represented by a mulberry leaf. Mulberries and figs belong to family Moraceae, which is in the rose order, along with rose, elm, buckthorn, hemp, and nettle families. On the other hand, the diagram fits on two pages. It have to be much larger to be more comprehensive. All-in-all, the book is delightful and will provide lots of fun browsing. You will have to tell children that the page on fungi is a holdover from earlier definitions of botany.

Perhaps you would like to do a Tree of Life diagram for the flowering plants. There is a good one in the book, Botanicum by Katie Scott and Kathy Willis. It is part of the Welcome to the Museum series from Big Picture Press (no relation to Big Picture Science), and it was published in 2016. The branches are correct on the diagram (pages 2 and 3), but they have just one example for each branch, and the orders are not stated. The example represents a whole order, which leaves out a lot. For example, the rose order, Rosales, is represented by a mulberry leaf. Mulberries and figs belong to family Moraceae, which is in the rose order, along with rose, elm, buckthorn, hemp, and nettle families. On the other hand, the diagram fits on two pages. It have to be much larger to be more comprehensive. All-in-all, the book is delightful and will provide lots of fun browsing. You will have to tell children that the page on fungi is a holdover from earlier definitions of botany.

The photos of families from my newly revised Flowering Plant Families Slides can be used to create a Tree of Life that has many orders. It gives a broader look at the families than its predecessor, and it is still centered on the families of North America. There are over 400 families of angiosperms worldwide. You don’t need to worry about being anywhere near comprehensive when you introduce children to flower families. Select the main ones for which you have examples from your school landscape, in areas near the school, or as cut flowers. If you or your children want to see the full list, go to the Wikipedia article on APG IV system (Angiosperm Phylogeny Group IV).

I’m not the only one that advocates structuring botany studies around flowering plant families. Thomas Elpel has written a highly successful book called Botany in a Day: The Pattern Method of Plant Identification. It is further described as “An Herbal Field Guide to Plant Families of North America.” This book is in its sixth edition. It has color drawings as well as black and white ones, and these could be useful in classrooms. I have not recommended placing this book in the elementary classroom, however, because it includes many food and medicinal uses for wild plants. I do not want to encourage children to eat wild plants or use them as medicine.

I’m not the only one that advocates structuring botany studies around flowering plant families. Thomas Elpel has written a highly successful book called Botany in a Day: The Pattern Method of Plant Identification. It is further described as “An Herbal Field Guide to Plant Families of North America.” This book is in its sixth edition. It has color drawings as well as black and white ones, and these could be useful in classrooms. I have not recommended placing this book in the elementary classroom, however, because it includes many food and medicinal uses for wild plants. I do not want to encourage children to eat wild plants or use them as medicine.

Botany in a Day is available from Mountain Press Publishing in Missoula, Montana, which also carries Elpel’s flower family book for children, Shanleya’s Quest. This book is a great one for elementary classrooms, and I strongly recommend it.

Botany in a Day is available from Mountain Press Publishing in Missoula, Montana, which also carries Elpel’s flower family book for children, Shanleya’s Quest. This book is a great one for elementary classrooms, and I strongly recommend it.

Enjoy exploring and identifying the flowers!

Someone has posted my Tree of Life chart on Pinterest and suggested in the caption that it could be a substitute for the Timeline of Life. NOT SO! These are two different materials with two different uses.

Someone has posted my Tree of Life chart on Pinterest and suggested in the caption that it could be a substitute for the Timeline of Life. NOT SO! These are two different materials with two different uses.

The Tree of Life does not show details of life through time. It shows extant animals and their lineages. People may be confused because classification has an element of time now. We group organisms by their common ancestors. You can’t show relatives without some reference to time. My cousins and I share a set of grandparents, so we have a recent common ancestor. That’s what makes us closely related.

Classification has become systematics (more on that in a later post). Biologists do not show rows of evenly spaced boxes with no connections when they diagram a kingdom or other related life. Instead, they connect the boxes (or names) with a branching diagram to show which organisms share more recent common ancestors.

The Tree of Life chart is used much like a Five Kingdoms chart was. If you are still using a Five Kingdoms, Six Kingdoms, or heaven forbid, a Two Kingdoms chart, you need to change to a different kind of chart. A Tree of Life chart is used to introduce children to the diversity of life. When I give this lesson, I tell children that this chart has a branch for all the major kinds of life on Earth. (And you may have one precocious child who asks “What about viruses?” No, they don’t belong on the organisms’ Tree of Life. They have their own.)

I can envision directing children’s attention to the big, black branches and noting that they are all connected, and they all share a common origin. I would also say that there are many, many varieties of life, and we would have a hard time studying it all at once. Instead, we put certain branches together for the purpose of focusing on them. Three of these major branches are called kingdoms because they are all the descendants of a common ancestor. They are outlined with color rectangles – yellow for fungi, red for animals, and green for land plants. The other two rectangles show organisms that we put together for the purposes of study – purple for prokaryotes and blue for protists.

The Tree of Life is used for children ages 6-9 to show them the big overview of life. They enjoy putting the cards on the solid, colored rectangles. The text on the back of the illustrations helps children place the picture of the organism. To help them find the right place, the major section and the name of the branch are in bold typeface. Older children and even secondary level students can still use the Tree of Life, and they should have an opportunity to place the cards and discuss this chart. Do they see that animals and fungi are sister kingdoms? This is why treating fungal infections is so hard.

On the other hand, the Timeline of Life shows the organisms that have lived during the time periods of the Phanerozoic Eon. A few timelines may have a bit of the previous Late Proterozoic, but the major emphasis is on life since the beginning of the Cambrian Period. There is nothing other than a timeline of life that can show this. Unfortunately the traditional Montessori Timeline of Life is riddled with mistakes – omission of the five major extinctions, all extinctions shown as ice ages, indistinct organisms, no grouping of related organisms, and my worst pet peeve, converging red lines that seem to show several lineages being fused into one.

OK, enough attacks on the Timeline of Life. It is still an important material for children, and I think it is important to use one that is updated and corrected, either by the teacher or by a company that has carefully researched its product. The Timeline of Life helps children understand how life has changed through time. (One last rant – add the Devonian explosion of plants! During that period, the land turned green as plants changed from a low green fuzz to trees that bore seeds. The Devonian – It’s not just for fishes!)

As a reminder of what is available on my website to aid you, my Outline of Geologic Time and the History of Life has lots of information that will help you make an accurate, up-to-date Timeline of Life. The Tree of Life chart is still a free download – my gift to the Montessori community. My book, Kingdoms of Life Connected, is a teacher’s guide to the tree of life. I updated it in the fall of 2016.

May you and your children enjoy exploring the living world, both its diversity and its history.

In January, I visited Tucson, Arizona and enjoyed exploring the Sonoran Desert. The plants there show many adaptations to the heat and dryness. The cacti and palo verde trees are what I expected. What surprised me is that plants I thought would need much more moisture are also able to survive in that climate.

There had been rain before my visit, enough that several hiking trails were impassable because normally dry creeks were flowing. As usual, if you want life, just add water. The plants that need moisture to reproduce, the spore-bearing plants, came out of hiding and were thriving. I saw a number of different ferns, but those weren’t a big surprise. I had seen ferns growing from cracks in lava flows before. The key for ferns seems to be finding a moisture-conserving crack on the shady side of a rock outcrop.

The spike mosses, genus Selaginella, were fluffed out and green. One of their common names is resurrection plant, so you can image how they look when they are dry. Spike mosses are not true mosses. They are members of the club moss lineage aka the lycophytes. One Sonoran species, Selaginella rupicola, is called rock-loving spike moss. There were hillsides with many spike mosses protruding from cracks between rocks.

The mosses were looking very green and active. They are known for their ability to dry out and wait for water. They formed their green carpets out on more open ground and in sheltered rock overhangs. It was in one of the latter habitats that I found the big surprise. There were liverworts growing with the mosses.

Liverworts are the plants that have leaf pores that are always open. I think of liverworts as growing in habitats that have abundant moisture, not just isolated periods of wet weather. It is true that the liverworts in Oregon’s Willamette Valley survive the summer drought, but the humidity is never as low nor the temperatures as high as in the Sonoran Desert. The Sonoran liverworts are small, thalloid ones, much smaller than the ones native to western Oregon. They have the right appearance for a liverwort. They look like a flat leaf growing right on the ground, and they branch into two equal parts, which gives them a “Y” shape. They must have special adaptations and be very tough and resilient to live the desert.

Plants offer surprises in all habitats, not just the desert. You just have to take the time to look.

Last June, the organization that officially recognizes the discovery of chemical elements and their names announced the proposed names for the final four elements on the periodic table. This governing body, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), took suggestions from the discoverers of the elements and then it issued the proposal. People could submit comments about the names for several months, and then in November, the IUPAC published the names. This was the final step in making them official.

The element names and atomic numbers are: nihonium (Nh) for element 113, which is named for the country of Japan; moscovium (Mc) for element 115, named for Moscow, Russia; tennessine (Ts) for element 117, named for the state of Tennessee; and oganesson (Og) for element 118, named after a Russian scientist who helped discover several elements, Yuri Oganessian. A new periodic table with these names is available at the IUPAC website, https://iupac.org/what-we-do/periodic-table-of-elements/ .

So what does this mean for the Montessori classroom? Children are ready for the abstract idea of chemical elements when they are in their elementary years. When they get an introduction to the periodic table, it should include the full set of names. Children should get a least a brief story of how elements get their names and how governing bodies of science fields bring order to science knowledge.

Children need to know, however, that there are elements that one cannot see with one’s eyes. There are quite a number of elements that are known only by the energy, particles, and atoms produced when they undergo radioactive decay.

The image below is from my newly updated card set, Discovering the Periodic Table. It comes with two sets of cards for all 118 elements, one in color and one in black and white. The card on the left is an example of the color set, and in this case sodium's symbol is color-coded red to show it is one of the alkali metals. The other card is the back of the black and white card, and it shows the type of information given for each element - physical properties, chemical properties, and other information. The front of the black and white card is like the card on the left, but with the symbol only outlined.

I updated and expanded Discovering the Periodic Table last summer after the new names were announced. At that time I added some features to help children understand the nature of the largest elements. The elements that cannot be made in visible quantities have symbols with a dotted outline rather than a solid one. The smallest of these is astatine, atomic number 85. Scientists have calculated that if one could make a piece of astatine, it would instantly vaporize itself because of the energy released by its vigorous radioactive decay.

If you tell children this, they may wonder how such an element was ever discovered. If they don’t think of it, help them arrive at this question. We want children to think about what they hear and ask about how we know what we know. The idea to search for astatine came from its place in the periodic table. Mendeleev left a blank beneath iodine on his first periodic table, implying that there was another element in the halogen family. Researchers that first identified this element used a nuclear reactor to bombard bismuth, atomic number 83, with alpha particles. This added two more protons to bismuth nuclei, and produced a small amount of astatine, which quickly decayed. Later, when researchers knew astatine’s characteristics, and they were able to find tiny traces of it in uranium ores.

After astatine, the next element that can’t be made in visible amounts is francium, atomic number 87. The dotted outline symbols don’t show up again until atomic number 101, mendelevium. It and all larger elements cannot be made in visible amounts. Researchers have made so little of elements 104-118 that the chemical properties of these elements are also unknown. In the cards with color-coded symbols from Discovering the Periodic Table, elements 104-118 have gray symbols to show that there is not enough evidence to assign them to a chemical group such the halogens.

Your children may ask if more elements can be discovered. In theory there could be, but if someone does discover more elements, it will be bigger science news than any recent element discovery. Meanwhile, help 6-9 year-olds explore the common everyday elements with the cards set, Elements Around Us from InPrint for Children. The set, Element Knowledge, will help 9-15 year-olds learn element names, symbols, and several significant groups. This set includes the first 111 elements. You can add the names and symbols of the other seven if your children are interested. They certainly won’t see those symbols in any chemical formulas.

The second edition of my book, Kingdoms of Life Connected: A Teacher’s Guide to the Tree of Life, is available now. I wrote the first edition in 2008, and it was already time for an update this year. New information keeps coming in all fields of science. This leads to gradually evolving ideas, but change has been exceptionally rapid in the field of systematics, the study of the diversity of life.

The second edition of my book, Kingdoms of Life Connected: A Teacher’s Guide to the Tree of Life, is available now. I wrote the first edition in 2008, and it was already time for an update this year. New information keeps coming in all fields of science. This leads to gradually evolving ideas, but change has been exceptionally rapid in the field of systematics, the study of the diversity of life.

The flood of DNA information continues, and we must bear that in mind in our presentations. It would be better to state that the story you tell is based on the evidence scientists have gathered for now. In the future, there could be adjustments. This doesn’t mean that all the information about the Tree of Life will change. Instead there will be small alterations. The potential for change certainly doesn’t excuse the presentation of obsolete classifications as anything other than history.

One of the hardest tasks for my book revision was finding up-to-date children’s books about the diversity of life. I had to leave many older, but valuable, books on the resource lists. At least it is easier to find out-of-print books now than it was a decade ago. I also found that publishers have reprinted some valuable older books. They include Peter Loewer’s Pond Water Zoo: An Introduction to Microscopic Life. Jean Jenkins illustrated this book in black and white, and it has attractive, clear drawings of many protists, bacteria, and microscopic animals, along with text that upper elementary children can read. You will have to warn your children that the classification scheme presented, the Five Kingdoms, is obsolete, but the information about the groups of organisms is still quite good.

A forty-year-old book by Alvin and Virginia Silverstein, Metamorphosis: Nature’s Magical Transformations, has been reprinted by Dover Books. It has a chapter on sea squirts that shows the tadpole-like larval stage and tells about the life cycle of these chordates. I haven’t found another children’s book that tells this story. The black and white illustrations show how old the book is, but there didn’t seem to be a good alternative.

I know the pain of having to purchase a new edition of a reference book. My favorite biology textbook cost nearly $200, and I see the new edition, just published this month, is priced at $244. Yikes, that’s hard on the budget. If you own the first edition of Kingdoms of Life Connected, you will be able to purchase the ebook version – the pdf file – of the book at a reduced price. Please email info (at) bigpicturescience (dot) biz for information about how to do this.

I’m always happy to find children’s books that portray bacteria as something other than germs. In my recent searches, I’ve found three gems. Two of them came from Australia, but I found the shipping was quick. The publisher is Free Scale Network, and the books are sold by Small Friends Books http://www.smallfriendsbooks.com/. The authors are Ailsa Wild, Aviva Reed, Briony Barr, and Dr. Gregory Crocetti.

It’s not often that bacteria get to be the protagonists, but in The Squid, the Vibrio, and the Moon the heroes are bacteria that help a young bobtail squid evade its predators. The story is set near the Hawaiian Islands, and it is dramatic and engaging. The attractive illustrations do a great job of supporting the story. They combine scales and will need some explanation, but the size scale at the front will help children keep all the components of the story in perspective.

The second book, Zobi and the Zoox, is set in a coral colony on the Great Barrier Reef. The protagonist is a rhizobia bacterium, Zobi for short. The action takes place in a coral polyp named Darian. The personification of these organisms could be distracting, but it isn’t. It helps one keep the characters separate and follow the action. There’s plenty of action as the coral faces warming in the ocean.

Both of these books can give children a greater appreciation for the many roles that bacteria play in making the biosphere work. It is easy to say that bacteria are an important part of all ecosystems, but that statement needs to be followed with great examples of actual symbioses like these books provide.

These two books are 38 pages long, and they can be enjoyed as a read-aloud by beginning elementary children. Older elementary can read the books themselves, and even secondary levels can learn from them. There is a glossary and several pages of additional information in the back of the books.

The third book that would be a great addition for studies of the microbial world is Inside Your Insides: A Guide to the Microbes That Call You Home by Claire Eamer, illustrated by Marie-Eve Tremblay. It was just released this month. This book has a wide range of information about microbes – what they are, where they live, and what they have to do with us and our world. The illustrations are goofy and cartoonish, but they work well enough to help children picture what is going on. The information is accurate and current, something that is hard to find in any children’s science book, much less one on microbes. Upper elementary children will likely enjoy the corny jokes sprinkled through the book, but they will also find plenty of good information. You could read it to lower elementary children.

d.

d.

To help you with your botany studies, I’ve just revised and expanded my PowerPoint slides on flowering plant families. This file is a pdf that can be printed to make letter-sized posters of 20 flowering plant families. The slides include text that describes the features of the flowers, and they show photos of family members. To round out this material, I’ve added a representative photo of 48 other families or subfamilies from all branches of the angiosperms.

To help you with your botany studies, I’ve just revised and expanded my PowerPoint slides on flowering plant families. This file is a pdf that can be printed to make letter-sized posters of 20 flowering plant families. The slides include text that describes the features of the flowers, and they show photos of family members. To round out this material, I’ve added a representative photo of 48 other families or subfamilies from all branches of the angiosperms.  Perhaps you would like to do a Tree of Life diagram for the flowering plants. There is a good one in the book, Botanicum by Katie Scott and Kathy Willis. It is part of the Welcome to the Museum series from Big Picture Press (no relation to Big Picture Science), and it was published in 2016. The branches are correct on the diagram (pages 2 and 3), but they have just one example for each branch, and the orders are not stated. The example represents a whole order, which leaves out a lot. For example, the rose order, Rosales, is represented by a mulberry leaf. Mulberries and figs belong to family Moraceae, which is in the rose order, along with rose, elm, buckthorn, hemp, and nettle families. On the other hand, the diagram fits on two pages. It have to be much larger to be more comprehensive. All-in-all, the book is delightful and will provide lots of fun browsing. You will have to tell children that the page on fungi is a holdover from earlier definitions of botany.

Perhaps you would like to do a Tree of Life diagram for the flowering plants. There is a good one in the book, Botanicum by Katie Scott and Kathy Willis. It is part of the Welcome to the Museum series from Big Picture Press (no relation to Big Picture Science), and it was published in 2016. The branches are correct on the diagram (pages 2 and 3), but they have just one example for each branch, and the orders are not stated. The example represents a whole order, which leaves out a lot. For example, the rose order, Rosales, is represented by a mulberry leaf. Mulberries and figs belong to family Moraceae, which is in the rose order, along with rose, elm, buckthorn, hemp, and nettle families. On the other hand, the diagram fits on two pages. It have to be much larger to be more comprehensive. All-in-all, the book is delightful and will provide lots of fun browsing. You will have to tell children that the page on fungi is a holdover from earlier definitions of botany. I’m not the only one that advocates structuring botany studies around flowering plant families. Thomas Elpel has written a highly successful book called Botany in a Day: The Pattern Method of Plant Identification. It is further described as “An Herbal Field Guide to Plant Families of North America.” This book is in its sixth edition. It has color drawings as well as black and white ones, and these could be useful in classrooms. I have not recommended placing this book in the elementary classroom, however, because it includes many food and medicinal uses for wild plants. I do not want to encourage children to eat wild plants or use them as medicine.

I’m not the only one that advocates structuring botany studies around flowering plant families. Thomas Elpel has written a highly successful book called Botany in a Day: The Pattern Method of Plant Identification. It is further described as “An Herbal Field Guide to Plant Families of North America.” This book is in its sixth edition. It has color drawings as well as black and white ones, and these could be useful in classrooms. I have not recommended placing this book in the elementary classroom, however, because it includes many food and medicinal uses for wild plants. I do not want to encourage children to eat wild plants or use them as medicine. Botany in a Day is available from Mountain Press Publishing in Missoula, Montana, which also carries Elpel’s flower family book for children, Shanleya’s Quest. This book is a great one for elementary classrooms, and I strongly recommend it.

Botany in a Day is available from Mountain Press Publishing in Missoula, Montana, which also carries Elpel’s flower family book for children, Shanleya’s Quest. This book is a great one for elementary classrooms, and I strongly recommend it. Someone has posted my Tree of Life chart on Pinterest and suggested in the caption that it could be a substitute for the Timeline of Life. NOT SO! These are two different materials with two different uses.

Someone has posted my Tree of Life chart on Pinterest and suggested in the caption that it could be a substitute for the Timeline of Life. NOT SO! These are two different materials with two different uses.

The second edition of my book, Kingdoms of Life Connected: A Teacher’s Guide to the Tree of Life, is available now. I wrote the first edition in 2008, and it was already time for an update this year. New information keeps coming in all fields of science. This leads to gradually evolving ideas, but change has been exceptionally rapid in the field of systematics, the study of the diversity of life.

The second edition of my book, Kingdoms of Life Connected: A Teacher’s Guide to the Tree of Life, is available now. I wrote the first edition in 2008, and it was already time for an update this year. New information keeps coming in all fields of science. This leads to gradually evolving ideas, but change has been exceptionally rapid in the field of systematics, the study of the diversity of life.